The Constrained Tile Placement Algorithm behind Generate Worlds

This post describes the algorithm that powers Generate Worlds, a tool that lets users create and explore procedural worlds by building small sets of voxel tiles. In this post I’ll give an overview of the algorithm, and my next post will show that it compares favorably to competing methods in terms of speed and flexibility. For some background on what constraint-based procedural generation is and why it’s interesting, look at my previous post.

If you’d like to try your hand at creating procedural worlds using this system, consider buying Generate Worlds. If the price is too steep, read on, and this post will give you all the information you need to implement the Generate Worlds algorithm yourself.

Tile Sets

In Generate Worlds, each environment is assembled from a tile set. Tiles are simply small voxel models. Let’s start with an example. The image below contains 9 tiles. As you can see, each tile is made of voxels, which display as colored cubes.

If we put arrange these voxel models in a sensible way, we can make a little pastoral scene, as in the animation below. By “sensible” I mean that tiles fit together if their colors match along the touching edge.

The goal of the Generate Worlds algorithm is to perform this assembly quickly and automatically. Before considering the algorithm, let’s look at the problem setup.

Putting Tiles Together

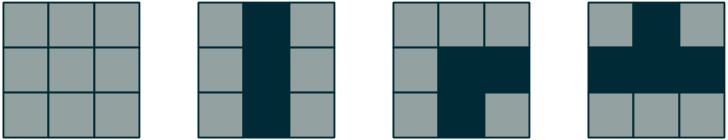

Consider a tile set containing the 4 tiles in the image below:

These tiles are analogous to the 3D ones shown in the previous section.

The Generate Worlds algorithm creates valid tilings by imposing one simple rule: If two tiles touch, all colors along the touching face must match. This rule formalizes the intuition that a human designer might use to construct a 3D world out of voxel tiles.

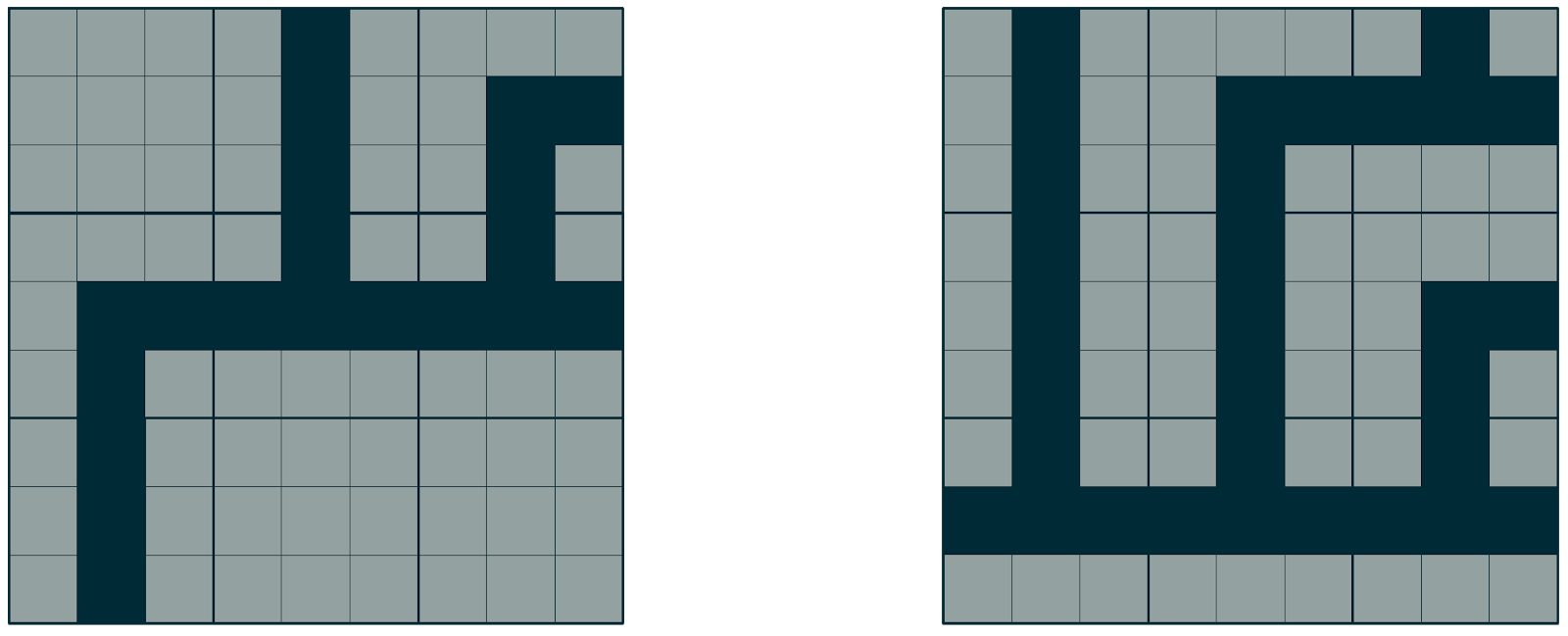

In a valid tiling of the 4 tiles above, light-colored cells will touch only light-colored cells and dark-colored cell will only touch dark-colored cells along tile borders. For example:

The example above on the right is invalid because a light square touches a dark square along the edge where the tiles touch. Below are two valid tilings generated with this tile set:

Creating a valid tiling turns out to be non-trivial in general. For instance, take the following simple, greedy strategy: We start with an empty grid. At each iteration, place a tile in some location by choosing a tile that is valid given the tiles that we’ve already placed. The diagram below illustrates the difficulty with this strategy.

By placing tiles without looking ahead at how placements affect future options, the greedy approach quickly gets stuck; in the diagram above, no valid placement is possible at the red location. This is the central difficulty: past placements can reduce current placement options to zero. We need some way to prevent placements that cause us to get stuck. The algorithm implemented in Generate Worlds starts by considering all tiles to be possible at all locations in the grid. If I place one tile in the grid, clearly some of those possible placements go away. Once the algorithm takes those possibilities away, it can reexamine the remaining possibilities and remove yet more tiles that are now incompatible with the smaller set of remaining possible tiles at neighboring locations.

Consider the example below. The algorithm starts with a 3x3 grid with a single tile placed in the center. The placement of this tile immediately implies that 9 possible tiles in the neighboring grid locations are impossible, so it removes them from consideration. Once these tiles are removed, it can remove tiles that are not compatible with any tile still under consideration in the neighboring grid squares. The red locations in the diagram highlight locations where tiles are removed because they are incompatible with all the neighbors still under consideration. If the algorithm continues this process until no more tiles can be removed, it gets to the state on the bottom left of the diagram below. As you can see, many tiles have been removed from consideration. If a tile placement strategy were to only choose tiles from these remaining groups, it would be considerably less likely to get stuck than it would when using the greedy algorithm I described earlier.

The problem with this approach is that it requires an expensive iterative process each time I place a tile. But note that any time I place the inverted T tile, the 19 tiles that I removed in the example above can be removed from consideration around that placement. I call the collection of tiles that remain under consideration around the tile after it is placed the allowed neighborhood for that tile.

Rapid Tiling by Caching Information

The key insight of the Generate Worlds algorithm is that the information gathered about a tile’s possible neighbors can be reused each time that tile is placed. For the inverted T-shaped tile above, for instance, we can remove 19 tiles from consideration in the eight surrounding grid squares as soon as that tile is placed by looking up a cached version of the allowed neighborhood for that tile.

For instance, in the example below, the algorithm is tiling a 5x5 grid by using the cached allowed neighborhoods of the 4 tiles. After placing the first tile, it removes the 19 tiles from consideration that we found to be impossible in the example above. After placing each tile, the possibilities not in the allowed neighborhood of the placed tile are removed from consideration.

Continuing in this way, we can tile the entire grid with only fast local updates to the sets of tiles still under consideration at each location.

Allowed neighborhoods can be as large as you want, allowing distant incompatible tiles to be removed from consideration each time a tile is placed. While generating the allowed neighborhoods is relatively slow, it only needs to be done once, and thereafter each tile placement takes time linear in the size of the neighborhood.

Extension to 3D

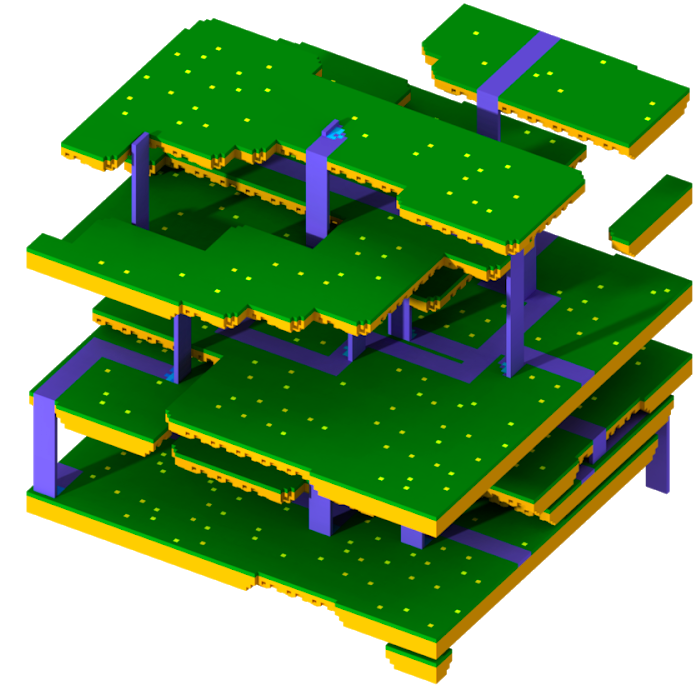

The Generate Worlds algorithm extends naturally to worlds with height. Instead 2D tiles that must match in color along their shared edges with 4 neighbor tiles, we have 3D tiles that must match in color along 6 faces with their neighbors. Consider these 3D tiles:

Assembling these tiles in 3D looks like this:

In this case, the allowed neighborhoods are 3D grids instead of 2D grids, and the algorithm generates them in an analogous fashion to what I’ve illustrated above for the 2D case.

Result Gallery

Below are images of worlds generated using implementations of this algorithm, along with brief descriptions.

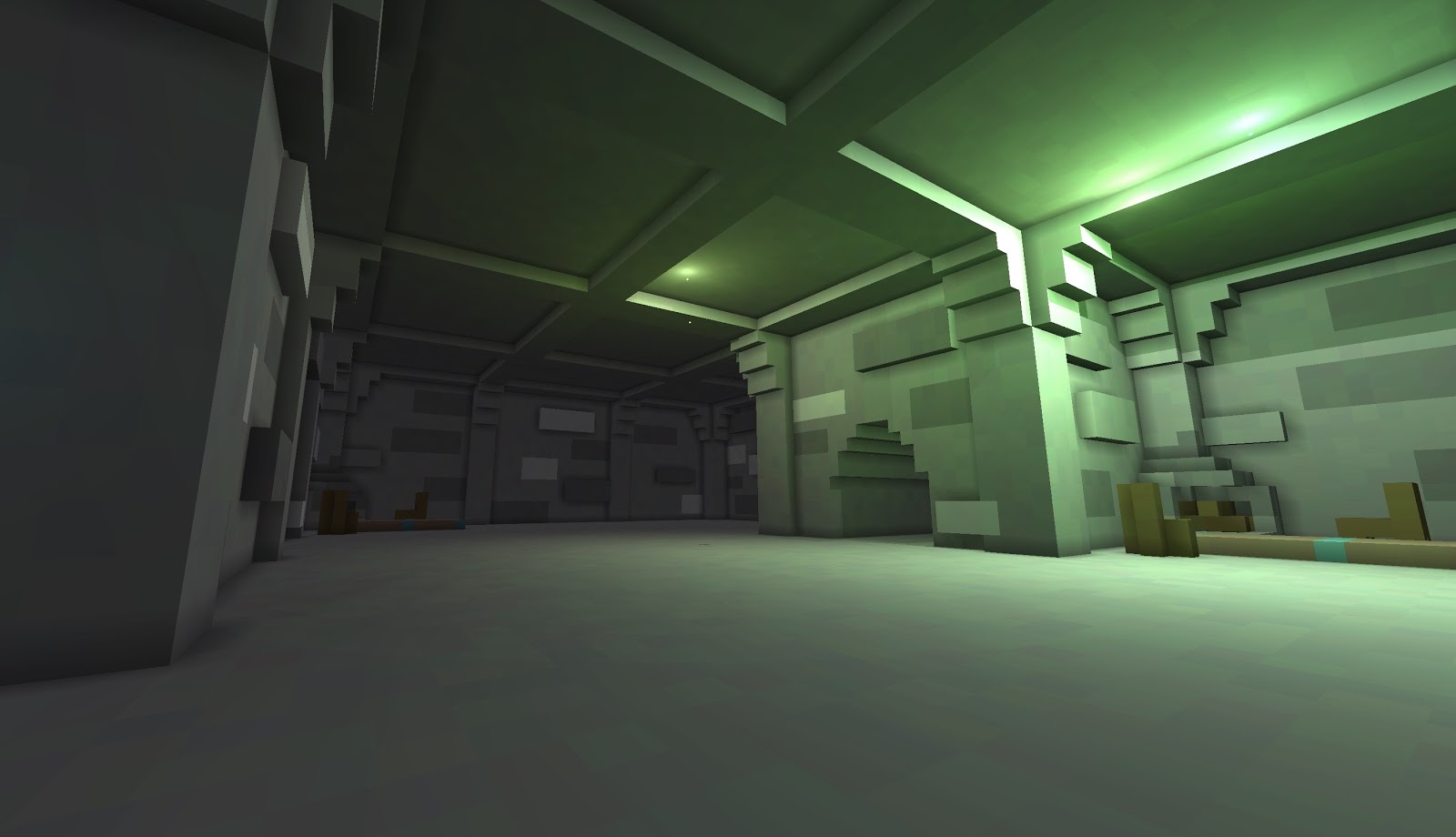

A screenshot from Generate Worlds showing a room with an exit. The ridges on the ceiling coincide with tile boundaries.

A screenshot from a separate tool I am building, which is also powered by the Generate Worlds algorithm, showing different types of rooms and passageways.

A similar world as above, but now in a cute isometric view

A world inspired by Dante’s ninth circle of hell: sinner frozen in a plane of ice. Rendered in MagicaVoxel.

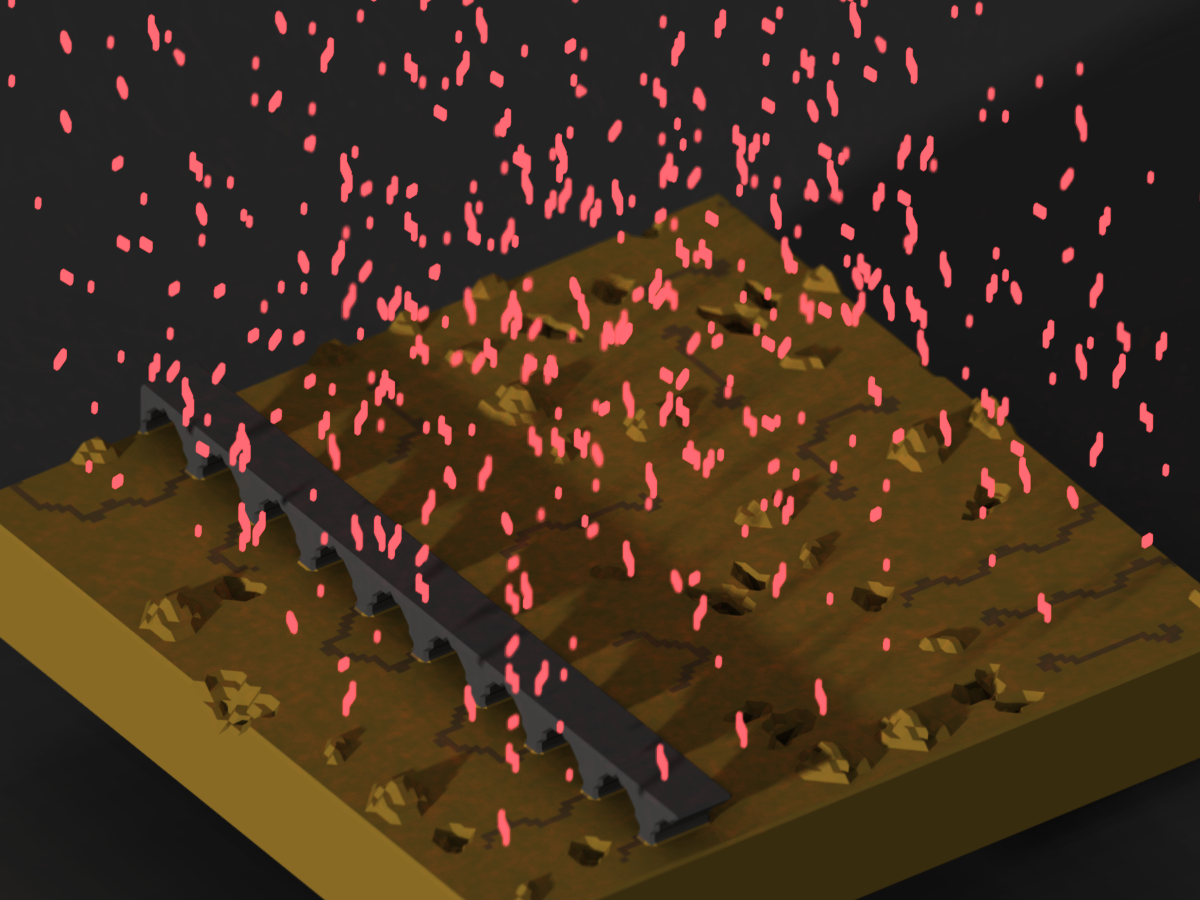

A world inspired by Dante’s second circle of hell: a landscape under burning rain, crossed by a bridge. Rendered in MagicaVoxel.

A world with grassy platforms with waterfalls and rivers. Rendered in MagicaVoxel.

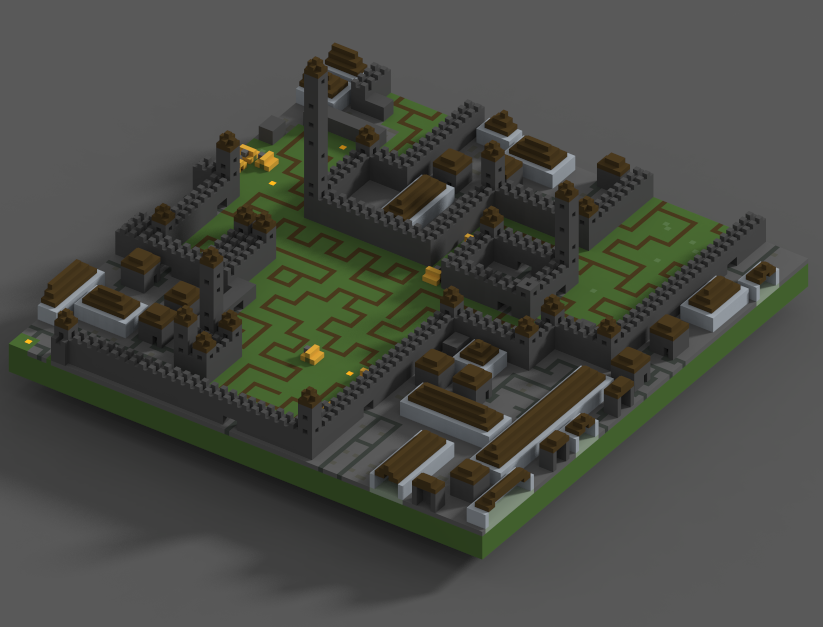

A medieval town landscape with buildings and walls. Rendered in MagicaVoxel.